An ancient Roman camp was constructed on the previous settlement to protect the road from the north, known as the Saltway, as well as an important ford leading towards British Camp. Situated on elevated ground above the floodplain, the camp served as a deterrent to the local tribes residing across the Severn River. With a capacity for around sixteen hundred soldiers, the camp utilized the ford for crossing, as evidenced by the discovery of wooden piles used for footholds during river dredging.

It is possible that a ‘vicus’, or village, developed around the camp to house the soldiers’ families and provide amenities such as shops or an inn, potentially marking the origins of the present village. Various artifacts from Roman times have been uncovered, including coins from the reigns of Emperors Caligula and Domitian, as well as a variety of pottery, both locally made and imported.

Evidence suggests that a section of the second legion was stationed in Kempsey, with the discovery of a Roman brick inscribed ‘LEG II CONSTANTINO’. Additionally, a Roman milestone honoring Emperor Augustus, likely erected during his rule (308-337 AD), was unearthed on the site and is now housed in the Worcester Museum.

Near the camp, a Roman burial site was found, with one notable grave belonging to a Romanized Briton, possibly a chieftain. This grave contained horse bones, a shoulder brooch, burial urns, and numerous pottery fragments, indicating a high-status individual. Traces of a villa were also found on the site.

Interestingly, the Romans exhibited ingenuity by constructing a bridge-like structure to cross the river at Kempsey. In 1844, remnants of oaken piles and planking were uncovered during Severn dredging, indicating the presence of a Roman bridge. Moreover, a Roman spearhead was discovered at this location, showcasing their advanced engineering capabilities.

The Saxons

The Romans remained in the country until approximately 410 AD, at which point they were recalled due to trouble at home. Following their departure, there was a period of relative peace, but the people of England faced frequent raids from the Norsemen, Saxons, and Vikings for centuries.

In 538, two Saxon brothers attacked Worcester, possibly leading to the fall of the Roman fort at Kempsey. Additional raids occurred along the River Severn in 680 and 868, with a field at Brookend known as Danes Close potentially linked to these events.

Although historical records from this time are scarce, it is known that some Saxons settled in Kempsey and the surrounding areas, as evidenced by local place names. Enclosures were known as “tons,” leading to names like Napleton and Pirton based on the crops grown there. Meanwhile, houses were called “halls” or “cots,” depending on the size and importance of the dweller. Trees also played a role in naming locations, with landmarks like ash trees giving rise to names like Nash.

Over time, the Saxons transitioned from raiders to peaceful settlers, eventually integrating into the general population of the area.

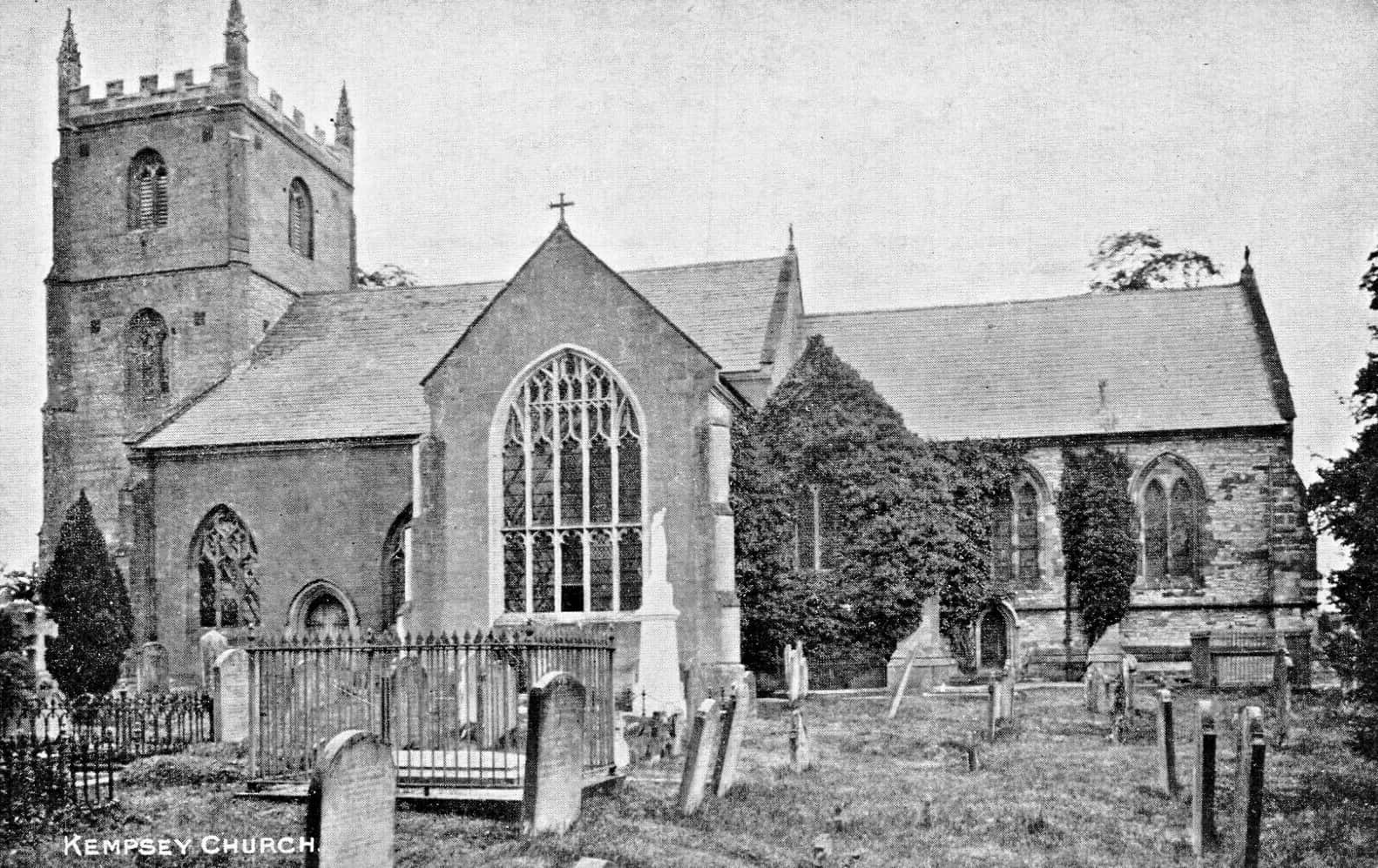

The Church

Kempsey was a part of the kingdom of Mercia and was deeply affected by the conversion to Christianity in 661AD. Following the arrival of missionary priests in Worcester in 655, a monastic community was established. In 680, Bosul from St Hilda’s Abby at Whitby became the first Bishop of Worcester, and a small religious community was founded in Kempsey around the same time, likely with a small wooden church.

Unfortunately, the church was later destroyed by Danish ships during a raid on Worcester, and the community in Kempsey likely suffered the same fate. In 799, a monastery was established in Kempsey under Abbot Balthun, and in 868, a chantry chapel was built to commemorate the departure of the Danes, although they returned shortly after to ravage Worcester.

After the monastery was destroyed, the bishops transformed the monastic lands into a memorial park, with the bishop’s palace located here during Saxon times. The river was a busy thoroughfare at the time, with monks and bishops being rowed from Worcester to Kempsey. A chapel attached to the palace was the site of Bishop Leofsy’s death in 1033, and documents from the time of Bishop John (1151-1158) mention a church in Kempsey.

It is evident that Christian worship has been conducted on or near this site for more than a thousand years, with Kempsey playing a significant role in the early Christian history of the region.

The Doomsday Book

The monasteries of Worcester and Kempsey, along with the surrounding parishes, were combined to create the Manor of Kempsey in the Oswaldstow hundred. The Bishops of Worcester held the position of Lords of the Manor for over a century. Following William, Duke of Normandy’s victory over King Harold at Hastings in 1066, he was crowned king of England and granted land to his followers, allowing them to build castles to control the populace. Saxon bishops were replaced by Norman chaplains, marking the end of Anglo-Saxon England, with the exception of the Saxon Bishop of Worcester, Holy Wulstan.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles describe William’s harsh rule, leading to the Domesday Book being compiled in 1085 to document land and livestock ownership throughout England.

Kempsey is noted in the Domesday Book, showing a decrease in value after the conquest. The entry for Kempsey lists its holdings, including hides, ploughs, villagers, smallholders, slaves, meadow, woodland, and the overall value of the village.

Royal Visitors

Looking out over the undulating meadows of Kempsey, it’s hard to believe that three kings of England were once entertained with the utmost hospitality befitting their royal status. According to historical notes by R.C. Purton, Kempsey was a place where “mitred lords of the manor kept their court in a splendor scarcely less regal” than that of royalty.

The first king mentioned is Henry II, the first Plantagenet, who inherited a fractured kingdom and a tarnished crown. Determined to restore royal power and prestige, he focused on establishing a sense of justice by implementing new legal systems such as juries, royal writs, and itinerant judges. His efforts laid the foundation for the English legal system and provided access to justice for all.

Henry III, on the other hand, was described as a man with grand ambitions but mediocre abilities. His reign was marked by heavy taxes, bankruptcy, and a power struggle with his barons. Eventually, the barons led by Simon de Montfort seized control, setting up the first parliament to limit the king’s power.

Lastly, Edward I, known as the “Law Giver,” was a formidable ruler who subjugated Wales and nearly conquered Scotland. He reformed the legal system, suppressed corrupt practices, and made his crown the most powerful in Europe. Even he visited Kempsey multiple times, showing his appreciation for the hospitality he received.

In conclusion, these three kings left a lasting impact on England’s history and were once guests in the regal setting of Kempsey. Their visits serve as a reminder of the rich historical heritage of the area and the importance of upholding justice and royal prestige.

The Civil War

The tension between King Charles and Parliament had been escalating for years. Parliament was increasingly frustrated with the king’s actions, including raising taxes without consent, imprisoning individuals without trial, and maintaining a standing army. By 1640, disagreements over religion, politics, and trade had reached a breaking point. The conflict eventually led to the English Civil War in 1642, with Royalist forces facing off against Parliamentarian troops.

Kempsey found itself quickly drawn into the conflict, as Colonel Nathaniel Fiennes and Colonel Sandys led a detachment of Lord Essex’s Parliamentary army through the area in September 1642. Though the outcome of the battle at Powick Ham remains uncertain, it’s likely that Prince Rupert emerged victorious. Fleeing soldiers from the battle sought refuge in Kempsey.

The village was repeatedly called upon to provide provisions for Royalist forces in Worcester and assist in fortifying the city. Fines were issued to the constables for failing to fulfill these obligations, such as on February 1, 1644, when the junior constable was fined £5 for not sending enough laborers for fortification work.

During the siege of Worcester in 1646, loyalty to either cause waned as both Royalist and Parliamentary forces resorted to raiding the surrounding area for supplies. After Charles I’s execution, Kempsey was sold to friends of Shakespeare for £75.12.6. The rent collected in 1649 totaled £81.12.6, raised from various sources including leaseholders, freeholders, and fines.

Kempsey changed hands once again in 1659, purchased by Christopher Meredith of London for £1812.5.10. During Cromwell’s rule in the Commonwealth period, strict Puritan values were imposed, leading to fines for activities like growing tobacco in Kempsey. Interestingly, it was discovered that Kenelm Winslow, grandfather of Edward Winslow who sailed on the “Mayflower,” was a farmer and churchwarden in Kempsey. Many of his descendants now reside in the United States.

The planting of a Revolution Elm in Church Street marked the transition from James II to William and Mary on the throne. This historical period left a lasting impact on Kempsey and its residents.

Dick Turpin

Tom King, a drinking companion of Lord Coventry, shared a daring plan to rob the nobleman with Turpin, a bold and skilled thief. Turpin eagerly agreed to the plan and assured King that he would successfully carry out his part of the scheme.

As they awaited the arrival of the young nobleman at an inn, Turpin set his plan in motion by obtaining an axe from a blacksmith and blocking the road with a fallen tree. When the nobleman’s carriage approached, a horse spooked and the valet discovered the obstruction on the road, causing a delay.

Lord Coventry, awakened from his nap by the commotion, was frustrated by the obstacle and cursed the road surveyors for their negligence. He was unaware of the carefully orchestrated plan by King and Turpin to rob him until it was too late.

The scene was set for a thrilling and daring robbery, with Turpin ready to carry out the heist and King waiting in the wings to make their escape. The stage was set for a daring and audacious crime to unfold in the moonlit countryside.

Stevens and the boy rode back to the inn on the uninjured horse. As they were leaving the lane, a man emerged from behind a tree and threatened them with a pistol, demanding their money and valuables. Lord Coventry refused to hand over a miniature of a lady he carried with him, but eventually agreed to pay thirty guineas in exchange for keeping the precious item. The highwayman, Dick Turpin, quickly presented the order to Lord Coventry’s agent and received the payment. The next night, Turpin met his friend to divide the plunder, which included the miniature of Mary Thornton.

Facts about Dick Turpin: Richard “Dick” Turpin, born in 1705 and baptized in 1795, was a notorious highwayman and horse thief. He was married to Mary Millington and was hanged in 1739 in York for his crimes. Turpin committed murder and highway robbery before going into hiding in Holland to avoid capture. Upon his return to England, he posed as a horse dealer under the name Palmer. Eventually, his true identity was revealed, leading to his arrest and subsequent hanging in York.

Windmill Lane

Kempsey’s Historic Windmill Lane Revealed in Rare Photograph

In a fascinating discovery, the true origin of Windmill Lane in Kempsey has been uncovered, thanks to a stunning photograph taken almost 150 years ago. The photograph, captured by pioneering photographer Benjamin Brecknell Turner between 1852 and 1854, showcases the Kempsey Windmill that once stood proudly in the area.

Despite the windmill being pulled down 126 years ago, the image has remained a cherished part of the photography collection at London’s prestigious Victoria & Albert Museum. Martin Barnes, assistant curator of photographs at the museum, believes that it is the earliest known photograph of Kempsey.

The location of the windmill was pinpointed with the help of Ron Sears, a longtime resident of Windmill Lane, who met Martin Barnes during his visit to Worcester. Barnes was thrilled to find the Sears’ home and garden as the exact spot where the historic windmill once stood.

Kempsey Windmill is just one of the many Worcestershire villages featured in Benjamin Brecknell Turner’s collection. Martin Barnes is currently compiling a book titled “Rural England Through Victorian Lens – Benjamin Brecknell Turner,” set to be published next month by V&A Publications. The book will showcase Turner’s remarkable photographs of rural England during the Victorian era, shedding light on the country’s rich history and heritage.